|

| A REFUGEE CAMP IS A REFUGEE CAMP IS A REFUGEE CAMP |

Adopted by General Assembly resolution 1514 (XV) of 14 December 1960

The General Assembly,

Mindful of the determination proclaimed by the peoples of the world in the Charter of the United Nations to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

Conscious of the need for the creation of conditions of stability and well-being and peaceful and friendly relations based on respect for the principles of equal rights and self-determination of all peoples, and of universal respect for, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language or religion,

Recognizing the passionate yearning for freedom in all dependent peoples and the decisive role of such peoples in the attainment of their independence,

A ware of the increasing conflicts resulting from the denial of or impediments in the way of the freedom of such peoples, which constitute a serious threat to world peace,

Considering the important role of the United Nations in assisting the movement for independence in Trust and Non-Self-Governing Territories,

Recognizing that the peoples of the world ardently desire the end of colonialism in all its manifestations,

Convinced that the continued existence of colonialism prevents the development of international economic co-operation, impedes the social, cultural and economic development of dependent peoples and militates against the United Nations ideal of universal peace,

Affirming that peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon the principle of mutual benefit, and international law,

Believing that the process of liberation is irresistible and irreversible and that, in order to avoid serious crises, an end must be put to colonialism and all practices of segregation and discrimination associated therewith,

Welcoming the emergence in recent years of a large number of dependent territories into freedom and independence, and recognizing the increasingly powerful trends towards freedom in such territories which have not yet attained independence,

Convinced that all peoples have an inalienable right to complete freedom, the exercise of their sovereignty and the integrity of their national territory,

Solemnly proclaims the necessity of bringing to a speedy and unconditional end colonialism in all its forms and manifestations;

And to this end Declares that:

1. The subjection of peoples to alien subjugation, domination and exploitation constitutes a denial of fundamental human rights, is contrary to the Charter of the United Nations and is an impediment to the promotion of world peace and co-operation.

2. All peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

3. Inadequacy of political, economic, social or educational preparedness should never serve as a pretext for delaying independence.

4. All armed action or repressive measures of all kinds directed against dependent peoples shall cease in order to enable them to exercise peacefully and freely their right to complete independence, and the integrity of their national territory shall be respected.

5. Immediate steps shall be taken, in Trust and Non-Self-Governing Territories or all other territories which have not yet attained independence, to transfer all powers to the peoples of those territories, without any conditions or reservations, in accordance with their freely expressed will and desire, without any distinction as to race, creed or colour, in order to enable them to enjoy complete independence and freedom.

6. Any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations.

7. All States shall observe faithfully and strictly the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the present Declaration on the basis of equality, non-interference in the internal affairs of all States, and respect for the sovereign rights of all peoples and their territorial integrity.

I really try every now and again to remind whoever is reading this stuff I put out about the on going and seemingly never ending struggle in the Western Sahara. I just don't get why it receives so little attention. The parallels between the Sahrawi people and the Palestinian people are too similar to provide a rational explanation for the widespread outrage and solidarity movement with one and the lack of such with the other. What's the deal?The General Assembly,

Mindful of the determination proclaimed by the peoples of the world in the Charter of the United Nations to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small and to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

I suppose there would be more attention paid to the Sahrawi if their oppressors were the Israelis. I hate to say that, but I think it is true. Always best in the world today, as far as picking up support, if your battle is with the Jews, er, scratch that, of course, I mean the zionists, right? Kind of ridiculous, but obviously, at least, somewhat true.

Personally, I don't care whether an oppressor is a Jew or a Muslim, an American or an Iranian, a zionist, a Hindu nationalist, A fundamentalist Jihadi or the Moroccan monarchy. Makes me no never mind. I am ready to oppose and expose them all as best I can.

I am not making light in any way of the long struggles of the Palestinian people, nor am I here to let the Israelis off the hook, but come on people can't we find room for solidarity with both the Palestinians and the Sahrawi? Can't we find enmity for both the Israelis and the Moroccans.

Maybe, someone can explain the disparity differently and I am willing to listen, but in the meantime, the following is from Souciant.

Military occupations bring certain themes to mind: human rights abuses; poverty; crowded refugee camps, and so on. Geographic references are equally synonymous: Palestine, Kashmir or West Papua, to cite the most recent example. Rarely, if ever, is the miserable situation in the sparsely-populated province of Western Sahara cited.

This is hardly surprising, given that the issue has long been ignored by the media, and by the international community. Statements of concern have been plentiful from UN members, in particular from African Union states. However, pitched against French meddling, and the effective backing of the Arab League and the US, this state of affairs looks set to continue.

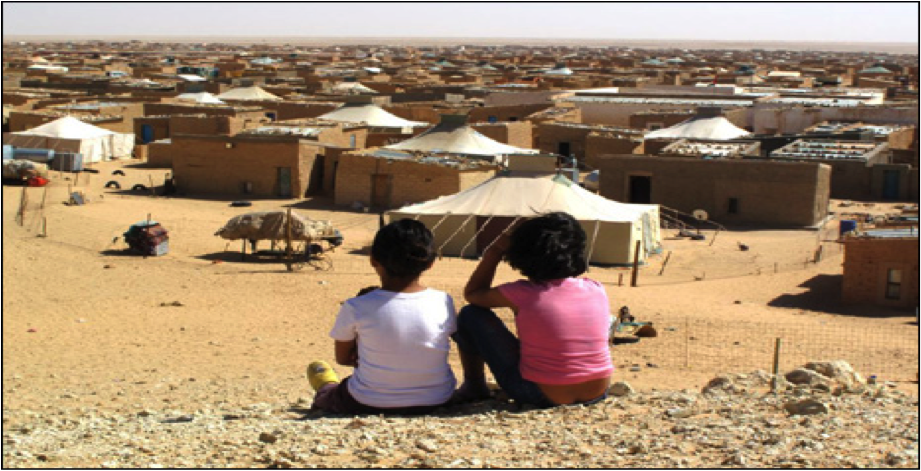

Yet the bitter plight of the dispossessed Sahrawi people, living in refugee camps in Africa’s last de facto colony, demands far more attention than it has received from the world. Living under the thumb of the occupying Moroccan military since a takeover by Rabat in the 1970s, the local people are now being demographically overwhelmed by Moroccans encouraged to settle in Saharan towns. The effect, as it is in the West Bank, is to create a residential obstacle to a reversal of the status quo.

A UN-sponsored Sahrawi referendum on the occupation is officially waiting to take place as a consequence of the ceasefire agreements between the Polisario Front, a separatist rebel group, and Moroccan forces. The vote is seriously overdue: it was meant to have taken place in 1992. Since that time, the Sahrawi have remained impoverished, subjugated and virtually hopeless for an improvement in their situation. Meanwhile, the occupiers have benefitted from their partnerships with the West, while the latter keeps all but silent on the gravity of Sahrawi suffering.

One person who has not neglected to critically address this issue is Stephen Zunes. Together with Jacob Mundy, the University of San Francisco political science professor produced one of the more recent books on the subjects: Western Sahara: War, Nationalism, and Conflict Resolution (Syracuse University Press, 2o10.) Talking to Souciant, Zunes described Morocco’s occupation as amounting to “the worst police state [he’d] ever seen.” I began by asking Professor Zunes two of the more pertinent questions on the issue: Why does the Western Sahara suffer from such neglect, and can we expect things to change in the near future?

****

Zunes: One of the things that gives me the most hope about the Western Sahara is (what’s happened in) East Timor. That was incredibly obscure for a long time, [and] the oppressor was allied with Western governments. You can imagine if Iran or Zimbabwe was doing what Morocco is doing, the whole thing would be a different story. But the Maghreb just doesn’t get the same attention as events in the Middle East.

Souciant: Do you think that may be because there haven’t been the sort of bloody events of the magnitude ofOperation Cast Lead?

Zunes: There’s certainly political repression. People who try and demonstrate [against the occupation] get brutally beaten and tortured, but we don’t have the massacres on the scale of East Timor. We do have a diaspora population that’s huge. It’s no fun living in a refugee camp in the middle of the Sahara for forty years.

Souciant: What is the West doing about this issue?

Zunes: Not much. The French are probably the worst culprits, with the United States coming second in terms of the major powers. The French are the ones who blocked the UN from doing anything. Under Obama, the US have at least opened up to allow MINURSO [the UN team that oversees the peace process between the Polisario and Morocco] to report human rights abuses. But the French won’t even allow that.

Souciant: Could you describe some of the more serious atrocities that have taken place during the occupation?

Zunes: The worst part was the invasion itself. The Moroccans had a scorched earth policy. That’s what created the refugee problem in the first place. They [ attacked] fleeing refugees and poisoned wells. It was a totalitarian state for the first twenty years or so [post-invasion,] and even recently. Morocco itself has liberalized a fair amount, compared to a lot of countries. But once you get south of the Draa River, you start getting roadblocks every thirty or forty miles. El Aaiuen [also known as Laayoune, major town in the north of the territory] itself is almost surrounded by police and military installations and jails, security is pretty constant I’ve been to sixty countries- including Iraq under Saddam Hussein- and Western Sahara is about the worst police state I’ve ever seen.

Souciant: How did the occupation begin?

Zunes: If you go back to the mid-seventies, during the previous twenty years there had been a wave of left-leaning, nationalistic military coups in the Arab world: Against King Farouk [of Egypt], King Idris [Libya] and several attempts against King Hussein [of Jordan.] A lot of people assumed that King Hassan in Morocco was shaky. In fact there were two coup attempts against him in the early seventies, which he barely survived. So Hassan felt the need to play the nationalist card. He thought that “liberating” the western provinces was a good nationalist cause. The Spanish were leaving anyway, promising self-determination to the people. Hassan got 300,000 Moroccans to do a symbolic walk into the country- that part was non-violent. But, while that was happening, armed columns were surreptitiously entering the territory. It was a great national cause. Everybody rallied round it. And it had the additional benefit of keeping the army as far away from Rabat as possible.

Souciant: Tell us a bit about your book on the Western Sahara.

Zunes: Basically, it was the most comprehensive English language book on the Western Sahara in at least a quarter century. Timothy Hodges was the last person to do a serious investigation. It covers the basic history and everything, but it really comes down to international accountability. It’s not a polemic. In fact, it is the most academic book I’ve ever written- but Jacob and I aren’t shy about presenting this as a self-determination struggle, as legitimate as the East Timorese, the Palestinians, the Namibians, other people who have been under occupation or suffered under colonialism. We give a hard time to the West. We give a particularly hard time to the US, as we’re Americans. We criticize the US for abrogating its responsibilities on this issue.

Souciant: Have you ever spoken to any US diplomats about this, or anybody who’s close to the White House?

Zunes: If they’re honest, they’ll point out that Morocco is a strategic ally of the United States. During the Cold War, they were an ally against Communism. Recently, they were allies in the war on terror. And the Polisario [or POLISARIO Front, POLISARIO being an abbreviation of the Spanish “ Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro”; an armed separatist organisation fighting to free the Western Sahara from Morocco] were never Communist or even Marxist. But they were definitely of that kind of left-wing, Third World, nationalist tradition, in the zero sum mentality of the Cold War era.

The issue right now [from an American perspective] is that they’re afraid what would happen to [Morocco's] monarchy if it lost the Western Sahara, because they have put so much into it. Initially, there was the war effort. Since then, they’ve subsidized Moroccans to live there. Now they outnumber the indigenous population.

Souciant: So it’s quite like what’s being done in the West Bank, then.

Zunes: Even more so. [Rabat] has had to endure international isolation on this issue. It quit the African Union in protest when it admitted the Western Sahara. It’s what’s prevented the Arab-Maghreb Union from happening because tensions with neighboring Algeria over this are so great. [NB: the Algerians are widely considered to support the Polisario Front, who have their headquarters in Algiers.] They’d be natural trading partners, but that’s kept things on the verge of war. It costs money, through building housing and providing tax breaks and so on. I could go on. It has been a huge sacrifice for the Moroccans.

But Rabat has gotten away with it because [the government] has convinced Moroccans, across the political spectrum that Sahrawis “welcome their liberation” and their “re-unification with the fatherland.” Anybody who says otherwise is an Algerian agent! It is amazing how many people have actually bought this line. But if the indigenous people of the Western Sahara had a free and fair referendum, the Moroccans would almost certainly lose that vote. People would get upset, because [Moroccans] have made all these sacrifices over the years [to keep the Western Sahara,] so they may ask “what else have we been lied to about?” And people are already frustrated by the corruption, the economy and everything else. I think that [the government] is concerned that there’d be a serious backlash.

Souciant: What do you think would bring about change for the people living under occupation?

Zunes: A lot of young Sahrawis are frustrated, calling for a resumption of the armed struggle. That’d be a disaster. The Polisarios are a secular-moderate group, but the Moroccans are already saying they are al Qaida- affiliated. If they did anything, it would play right into their hands.

Souciant: What sort of religious identity do the rebels have?

Zunes: They are Sunni, mainly. But they have always being nomads, they have never had an Emir or Sultan, and Islam has never been a state religion for them. When any nation has a state religion, it can be used to justify the status quo. Even though they are very observant Muslims, they see religion as a relationship between God and the individual. Women have equal rights to inheritance and divorce. They keep their maiden names. They’re in leadership positions. The role of women is very different [to the Moroccans.] That was one of the first things I noticed.

Souciant: What sort of ethnic identity do the Sahrawi people have?

Zunes: Like most Moroccans, they are a mixture of Arab Berber people. They have a very different dialect of Arabic. It’s almost impossible for Moroccans to understand them. Their food and clothing is different.

Souciant: Socially, how would you characterize them?

Zunes: Nomadic people are by nature very generous, because that is how they survive. If you’re not helpful to others, that’s how communities die. The Sahrawi really are kind. They are incredibly grateful to anybody, particularly if you’re American, for any kind of help you give them. I get fan mail all the time from Sahrawis that I have never even met. It’s a wonderful culture.

Photographs courtesy of Fronterasur, Saharauiak and sarlin/e. Published under a Creative Commons license.

No comments:

Post a Comment